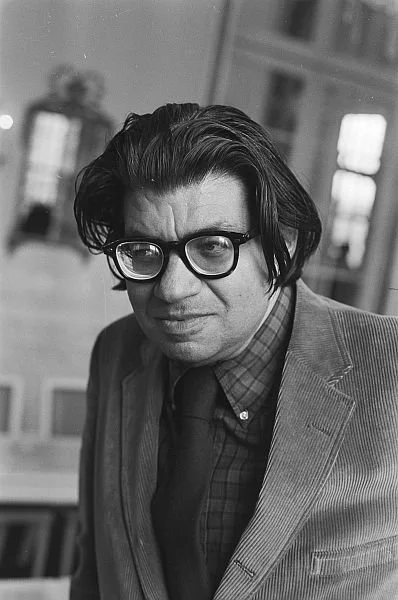

It wasn’t until sometime early last year that I learned a recording of Shostakovich’s First and Ninth symphonies played by the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra conducted by Rudolf Barshai existed. His cycle with the WDR Symphony Orchestra of Cologne is well known and remains competitive, even nearly 30 years since it was first issued. Perhaps because it has long been available at budget price (although it was recently reissued on SACD in Japan) and frequently packaged as part of various Shostakovich omnibuses aimed at entry level collectors, the stature of Barshai's cycle may have diminished somewhat. At least I haven't heard critics mention it as much as they did in the 2000s, when it was practically a default recommendation. Admittedly, with the fecundity of the Shostakovich discography this century, I've also contributed to this relative neglect, although in the last few years I've renewed my delight in Barshai’s Shostakovich. Aside from his WDR cycle, Barshai also made live recordings of Shostakovich’s Fourth, Fifth, and Seventh symphonies with German and Swiss orchestras that are worth hearing. (Not to mention his studio Eighth for EMI.)

This Canadian recording is no less rewarding. Barshai draws rich tone from the Vancouver strings, as well as spirited playing from the winds. Just listen to the trombonist in the first movement of the Ninth, whose constant interjections sound satisfyingly and appropriately “out of pocket”, to use the Gen-Z parlance. I’ve listened to this Ninth several times in the past month and, each time, it reinforces my opinion that it’s one of the best in the discography. Good recordings of this symphony aren’t hard to come by, but this Ninth in Vancouver is really special.

Barshai’s Vancouver Shostakovich First is quite good, too, although not on the same level. The first movement starts off well enough, with characterful winds, especially trumpet and clarinet, but the gait of the second theme drags a bit, and when the climaxes arrive later the mood never breaks free from a general stolidity at odds with the score’s mood. Youthful energy is also lacking in the scherzo, though the Vancouver Symphony played it with impressive clarity of articulation, and the piano climax here has a fearsomeness that is not too often heard. Where the performance really grabs one’s ears is in the “Lento”, which Barshai convincingly directs with an implacable gravitas suggestive of Tchaikovsky or Mahler. Young man’s music it is not, at least in this recording.

This CBC disc is so good overall that one would never guess that by the time it was made the Vancouver/Barshai relationship was not only already on the rocks, but on the verge of ending acrimoniously.

It had begun auspiciously enough back in 1984, when Barshai was selected by the Vancouver Symphony to succeed Akiyama Kazuyoshi (another excellent conductor I’ll probably write about some day). Echoing a well known quote by Shostakovich, Barshai told the press that the Vancouver Symphony would play “everything from Bach to Offenbach and more, including 20th-century composers”. Among those composers he hoped to program were Alexander Lokshin and Mieczysław Weinberg — esoteric music for a mid-tier North American orchestra of the 1980s. “Are Vancouver audiences ready for such introductions?”, a writer for the Canadian Press wondered.

Apparently not, as it turned out, but that would be the least of Barshai’s problems.

Even before the upbeat was signaled on the first, hesitant notes of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony at Barshai's Vancouver debut as music director, troubles were mounting. The orchestra was operating with a deficit of over US$600,000 (approximately US$2 million in 2026); an auditor projected an additional six-figure loss for the 1985–1986 season. A dramatic decline for an orchestra that a decade before had boasted the largest subscription base of any North American orchestra. According to another audit from 1982, management was bloated far in excess of the orchestra’s needs. On top of that, it reported that they squandered funds on expenses and interest-free personal loans. The revelations provoked the musicians of the Vancouver Symphony to threaten a strike, their second in less than five years. Management responded by locking the musicians out. Calm was restored after Barshai offered to take a pay cut in order to aid the orchestra, which led to a compromise that allowed operations to continue. It was a gesture as noble as it was timely — and went unreciprocated by management.

Barshai outwardly continued to maintain his resolve to make the Vancouver Symphony a “world-class ensemble”, in spite of the challenges. He might have succeeded had he not committed a misstep of his own: firing the orchestra’s concertmaster and one of its horn players, both well liked by personnel. Whatever feelings of goodwill that existed were poisoned once and for all. The feuding between Barshai and the orchestra’s musicians soon made local, then national headlines, capped by the publication of an internal poll that was effectively a vote of no-confidence against Barshai.

Amidst this chaos, the number of subscribers to the Vancouver Symphony continued to plummet and its deficit widened to nearly US$2 million (approximately US$6 million in 2026). In 1988, when their CBC CD of Shostakovich symphonies was issued, matters reached a point of no return. After months of grumbling, the orchestra’s board voted to refuse Barshai an extension of his contract, with the majority largely blaming him for the orchestra’s budget shortfall, despite audits that stated otherwise.

Barshai had his supporters and they took to the press to rally for his cause. One of them was Dennis Culver, the orchestra board’s president. In an interview with the music critic of the Toronto Star, Culver disagreed with his view that Barshai “failed to exert a charismatic presence during his three years in [Vancouver]”. Whatever issues the conductor may have had, Culver said, were nothing but “a pimple on the face of the world”. Instead, he cited ongoing economic problems in British Columbia, aging subscribers, and the failure of the orchestra’s marketing team to cultivate new listeners.

While the ink of the interview was still wet, the Vancouver Symphony declared bankruptcy, laid off its employees, and canceled the remainder of its season. Barshai retracted his initial threats of litigation against the orchestra, saying later through his attorney that he didn't want to inflict any harm on the ailing institution.

A few months later, the Vancouver Symphony came back from insolvency and resumed its activities. Denny Boyd, a Vancouver Sun columnist and Barshai defender, offered blunt advice to the embattled conductor’s potential successors: “Only sons-of-bitches need apply.”