After uncertainty and worry over the “Liberation Day” tariffs, the year 2025 is ending with my Japanese CD-collecting habit still going strong. Mostly. Because since Buyee now distributes the pain of the tariffs equally — whether one is a weeb buying plastic figurines of their “waifu” or a kook like myself placing sniper bids on oddball private-press CDs of Japanese regional orchestras — I’ve had to temper my whims. A recent release, entitled simply Mravinsky in Helsinki, however, was too good to pass up.

The label, Janus Classics (spelled with an idiosyncratic “v” in their logo), is one that I had only first heard about earlier this year by way of a batch of Paul Kletzki CDs that are currently on my “to buy” list. The big works on this Mravinsky set are Tchaikovsky 5 and Shostakovich 5, both of which have survived only piecemeal. Damage to the latter’s master tapes is so extensive that the entire first movement is lost. What remains suggests that the performance, recorded live at the 1961 Sibelius Festival, had it survived whole, would have been the best in Mravinsky’s discography. So just a curiosity for die-hards then, right?

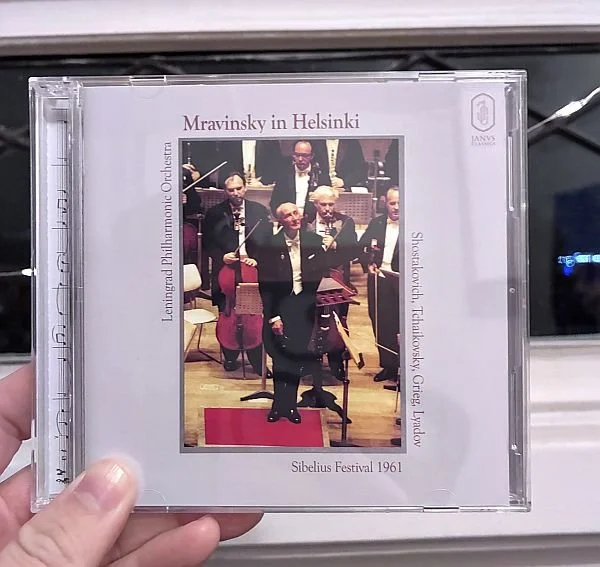

Janus’ high production values, first of all, are impressive. Classical music CD covers are often ugly, even infamously so. The cover of Mravinsky in Helsinki, designed by Di Xiao, consists of a photo of the conductor with the Leningrad Philharmonic, centered within an elegant gainsboro frame that features the album title, with the opening measures of the Shostakovich’s “Largo” embellished along the spine. Open the booklet and you find essays on the conductor and recordings, but before you even start reading them you notice the fine paper they’re printed on. As you begin to read the essays by (in order of appearance) Nam Li, Qiao Huang, Brian Wang, and Jiewei Xiong, you realize that this isn’t the glib fluff typical now even in specialist archival reissues. (That is if they’re even included at all.) Even the plastic jewel case — sturdier and thicker than usual — evinces the care that Janus took in producing this release. Already cutting corners at the turn of the century, record companies in the last decade have pushed it even further, lovelessly dumping recordings onto CDs as the kind of e-waste they apparently believe them to be. Janus, on the other hand, seems to believe that their releases aren’t just “content”, but living testaments of a past most of us were not fortunate to experience. Holding this Mravinsky in Helsinki set in my hands one thing was clear: we’ve come a long way from the bad old days of labels like Gramofono 2000, Iron Needle, Doremi, and Classica d’Oro.

Conductors from yesteryear, unlike those of today, indulge in dramatic interpretive shifts that are rewarding to listen and study. At least that’s how obsessive collectors like myself justify the purchase of yet another live Beethoven 5 conducted by Furtwängler. (Maestros as impulsive and mercurial as Knappertsbusch, the wild man of the podium, are rare in any age.) Mravinsky, as his widow told the DSCH Journal in 2002, was different:

Each time Yevgeny Alexandrovich immersed himself in a score he had studied before, he would discover new nuances and colors, just as a geologist strips off layer after layer as he works towards the discovery of true facts. He always strove towards the essence of a work and for a high standard of performance, hopefully revealing a new aspect of the composer and enriching our understanding of him.

For a listener seeking an immediate fix of musical thrills, Mravinsky’s lofty goals can seem unexciting. Which is maybe why his stock has plummeted with Western collectors since the 1990s, when his work was thoroughly exhumed by Olympia, BMG, and other labels. After an intense interest in the Russian conductor’s work in my youth, I too quickly moved on. But in April 2020, when businesses began to reopen after the pandemic lockdowns, I bought a clutch of Mravinsky CDs at Record Surplus in Santa Monica when they were liquidating their classical music section. These discs initiated a personal reexamination of the conductor’s discography that is ongoing.

Mravinsky belonged to the “fail, fail again, fail better” school of conducting: each of his performances of a given work was another step towards the realization of its unattainable ideal. To quote his widow:

Although Shostakovich was happy with the first performance, each time Mravinsky returned to the Fifth he introduced something new that he’d been able to draw from the depths of the piece: a nuance or an idea. In Mravinsky’s hands the score underwent changes, just as human life changes. Even the composer’s metronome markings, after repeated performances of the symphony, adapted to the atmosphere, like a human pulse.

Rather than mount the podium as a conquering hero, Mravinsky saw himself as a pilgrim repeating his ascent over and over again, his goal always visible over the horizon, yet ever out of reach. There is a vulnerability about this that I now find moving, even relatable. It’s amplified by the state of the Shostakovich 5 on this set — a survivor despite its scars — and the care with which the producers of this Janus release devoted upon it.