In my previous post, I briefly sketched out the shifting fortunes of Roy Harris and his Third Symphony, particularly here in the Los Angeles area. Tonight’s Los Angeles Philharmonic performance, conducted by John Adams, appears to be the first in the region since 1998.

By 1951, Harris’ reputation plummeted into what John H. Mueller, in The American Symphony Orchestra: A Social History of Musical Taste, described as “inevitable decline”. It wasn’t all bad news. Although no longer a virtual household name as during wartime, Harris continued to enjoy a significant level of prestige in American music. As late as 1973, Walter Arlen in the Los Angeles Times reported that BMI statistics confirmed over a thousand performances of Harris’ music the previous year — impressive for any living composer. His Third Symphony continued to be regarded by insiders as the flagship of the American symphony, at least through the 1970s. One of the work’s last great triumphs was on September 16, 1973, when it became the first piece of American orchestral music ever played in China (performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy). Harris himself also earned a growing list of official distinctions in his final decade: he was designated composer-in-residence at Cal State Los Angeles, composer laureate of the city of Covina, and later the state of California.

In spite of all this, Harris, even his Third Symphony, is today mostly forgotten to the general classical music public. What happened?

Criticisms of Harris’ stylistic development, as well as changing tastes among academics and listeners, were crucial in this decline. Reputations almost invariably sink after a composer’s death. Harris was no different and, despite the efforts of his widow and a few others, his music was quickly marginalized from the mainstream repertoire after his death in 1979.

Something else occurred in Harris’ final years.

A Los Angeles Times article from 1977 noted that Harris as a composer was concerned with matters of “social injustice”. Small wonder, then, that his final symphony, the Thirteenth, focused on that subject; it was composed for the National Symphony Orchestra in commemoration of the American bicentennial in 1976. Audiences expecting a rousing tribute were instead met with a work of concentrated outrage against the poisonous legacy of slavery and the Civil War.

Dan Stehman, in his Roy Harris: An American Pioneer, was circumspect about the symphony and its reception:

Although the Bicentennial Symphony is the least substantial of all Harris’ symphonies in musical invention, a clear manifestation of the declining powers that set in during the 1970s, it cannot be dismissed entirely, for it constitutes one of the strongest statements on racial intolerance yet made by an American composer. Though the work ends on a characteristically positive note, it is doubtful if audiences wished to be reminded, during the jingoistic excesses of the Bicentennial Year, of one of the ugliest episodes in American history, an episode whose ramifications, in spite of decades of progress, are still felt today.

The “Bicentennial Symphony” was, in fact, one of the worst failures of Harris’ career.

Perhaps sensing trouble, National Symphony music director Antal Doráti, who was scheduled to conduct the symphony’s premiere, pulled out citing illness; Murry Sidlin, resident conductor, took his place.

Harris’ Thirteenth Symphony was premiered at the Kennedy Center on February 10, 1976. “For the first time in my experience, there were boos at a National Symphony concert”, reported George Gelles, music critic for the Washington Star. He thought some of the audience’s fury at Harris was “justified” and added that the texts the composer set were “nothing but beauty and truth platitudes and racist exhortations”. Paul Hume in the Washington Post was not much more generous. He called the symphony “an embarrassment [...] a caricature of music, [...] and a travesty of all it sets out to do”.

If Harris was bothered by any of this, he didn’t make it obvious. “I don’t analyze my music,” he told an interviewer for WGMS. “That would be like pulling potatoes up to see if they’re growing”.

A subsequent performance that same month at North Texas University, to be conducted by Anshel Brusilow, was canceled at the last minute. Harris’ “Bicentennial Symphony” was replaced by a work by Benjamin Lees. According to news reports, the performance was cancelled because the sheet music for the symphony did not arrive, but given its stormy reception it isn’t hard to imagine that this reason may have been a face-saving ruse.

The symphony wasn’t performed again until 2009, when concert organizer and activist John Malveaux arranged a performance in Long Beach. Even then, ill feelings persisted. “[The symphony is] a piece of crap”, an anonymous patron told the Long Beach Press-Telegram. “I can see why it hasn't been done for 33 years”.

Harris’ Third and Thirteenth symphonies are distinct works, of course. Yet it’s difficult to avoid speculation: did the poor reception of the latter work contribute to the erosion of esteem of the former, and possibly of the composer’s work as a whole? Harris’ belief in the role of the American composer as a civic and artistic responsibility may have antagonized audiences in his lifetime, but that personal commitment to ideals beyond music is something that today’s listeners ought to reexamine with an open mind.

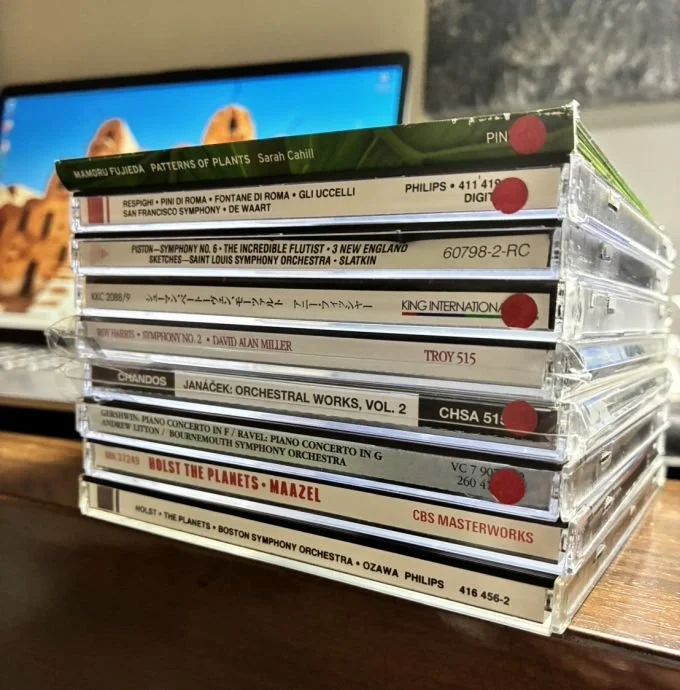

In the meantime, I’ll be at Disney Hall later tonight listening to the return of this great American symphony to Los Angeles.