As this year’s days dwindle down to a precious few, a music critic can dependably count on being asked by their editors to submit various journalistic round-ups summarizing their experiences over the past 12 months: Best recordings, most memorable concerts, and so on. Things are no different for me. The sun peeked out briefly, then slipped away beyond the horizon while my fingers busily typed away at drafts for two such articles to be published later in the week. In many respects, 2019 has been an unforgettable year for me personally; defining within it all the myriad connotations of the term “interesting times.” Like a popcorn kernel defiantly wedged in one’s molar, some experiences linger longer in the dusty and dimly lit corridors of memory despite themselves.

Take the ghastly production of The Magic Flute at Los Angeles Opera which I attended last month. A good friend and devoted lover of opera asked me shortly after this performance if I believed that the level of singing in this art form had declined in the last half century. A tricky question with predictably even trickier answers. On the whole, the calibre of singing today is probably higher than it has ever been. Conservatory and university-trained singers today in general have a holistic grasp of varied genres of their art—their instruments being able to turn on a dime with constant professionalism from Puccini, to Penderecki, to pop—that would have been unimaginable to an Urlus or Galli-Curci. It is enough to consider that there are probably more superlative classical singers active today in Southern California than there probably ever were in all of Central Europe during the heyday of Mozart and da Ponte.

So why the uncomfortable guilty conscience which dogs me after attending most operatic performances today? Is there something amiss today after all?

Next month, I’ll be walking down the street a few blocks from my home to see the Metropolitan Opera’s January production of Berg’s Wozzeck. Looking through the company’s website, I’m startled by the sight of all the performers, from the title lead down to the conductor: They are nearly all so glossily photogenic. Luigi Dallapiccola was already griping in the 1960s that opera had become something that people went to see rather than hear. Recalling the aforementioned Magic Flute, it was interesting to note that the vast majority of critical noise swirled around the visuals. Even the city’s de facto big boss of music criticdom was mostly agog over the sight of the thing, expending comparatively little space on the singing, and virtually nothing on the conducting and orchestral performance. Perhaps this was a polite omission. The Dorothy Chandler’s acoustics are notoriously awful, presenting a formidable challenge for any singer to surmount. That said, with the exceptions of the superb Tamino and Sarastro, the singing was mostly mediocre; one unfortunate singer was audibly being pushed beyond what her modest instrument was capable of. In such a situation, common today even in the most exalted opera companies, a regieoper production can arrive like a hero to the rescue, salvaging a middling musical performance with the trappings of dazzling visual distractions; the less relevant to the composer’s intentions, the better. It was quickly apparent at The Magic Flute, at any rate, that neither the singers, orchestra, conductor, nor even the composer were the stars of the show. Like junking a painting in order to admire the frame, the producers treated the opera as a prop to self-indulgently mug the spotlight for themselves. Not that the audience ever cares about such trifling details—they apparently loved it. Maybe it was best this way. In their own garish way, the producers may have felt that discretion was the better part of valor.

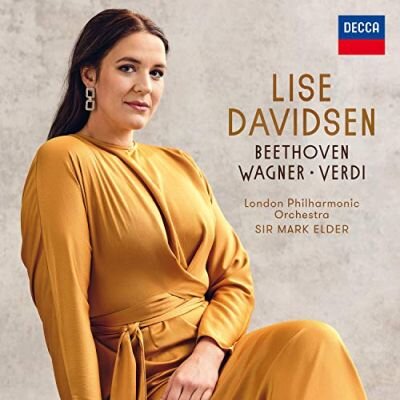

My thoughts also turned to Lise Davidsen, who lately has had the opera world at her feet. Comparisons to Flagstad and Nilsson, two of the mightiest voices that ever drew breath, run thick in print. Opera Now described her as being “a once in a generation Wagnerian.” Which makes me wonder whether these same critics have ever actually heard Flagstad and Nilsson—or even Davidsen for that matter. Receiving a copy of her Decca recording of Strauss’ Four Last Songs earlier this year, I was surprised to hear a fine, but ordinary voice which, moreover, is persistently hooty and wooly. If such a thing as “once in a generation Wagnerian” even is possible, then the few Millennials that care about such things may be made to wait just a little longer for the Isolde of their dreams. At least to my tin ears, Frida Leider she ain’t.

Way back in high school, I recall watching a Classic Arts Showcase clip of Jussi Björling and Renata Tebaldi singing through the great duet in La bohème. She was pleasantly matronly in appearance, if not quite the delicate young girl envisioned by the opera’s creators; Björling looked like Bob’s Big Boy. But what singing! Despite the cheap sets, their ages, and their bulging waistlines, they two suspended reality with every breath they took. This was no “performance”—in those few minutes before those ancient kinescope cameras, both of them melting underneath the blistering heat of the studio lamps, they simply were Mimì and Rodolfo.

Before going to bed last night, I thumbed through the pages of Lily Pons: A Centennial Portrait that my friend had gifted to me the day before. It could be argued that in some less than obvious (and flattering) ways, she was among the progenitors of today’s professional and drab style of singing. As even her admirers confessed, she earned her role at the Metropolitan Opera as much as for her singing as for her physical appeal. In her prime she was a remarkably beautiful woman, a quality which Pons shrewdly capitalized upon. Indeed, she won the Metropolitan job over another coloratura in great part because her competitor’s figure was “considered impossible for the standards of such a sophisticated audience.” Pons’ voice was nimble and sweet, if chalky white above the staff, with shallow low notes; she had neither the girlish color and evenness of production of Erna Berger, nor the stunning top notes which Erna Sack enjoyed. Nevertheless, a great singer she was all the same. Not only did Pons preserve her voice until well into her late years, but she also had made a careful study of her talents, taking close measure of its virtues and faults. “Actually, because I treasured and protected what God had entrusted to me,” she confided to a friend, “the silver flute in my throat lasted much longer than I could ever have hoped or anticipated.” There was something else, too, something which no conservatory training, no matter how thorough can teach: Natural charm in performance and sincere affection for music in general. Before embarking upon her career as a singer, she had been a formidable enough pianist in her teens to have earned a first prize at the Paris Conservatory. The totality of contextual thinking that the piano fosters—to consider not one, but multiple threads of musical thought, and weave them together into a cohesive whole—stayed with Pons her whole life, allowing her to become an ideal ensemble player who humbly understood that hers was simply another texture, however important, in the fabric that makes up an opera. In spite of her reticent musicianship, she adroitly manipulated the press to her advantage, becoming that which few opera singers even in those golden years were able to achieve—a genuine public figure, a star, and deservedly so.

A few years before her sudden death from pancreatic cancer in 1976, Pons reflected on the fading of the artistic values that had shaped her craft, as well as those who came before her: “You and I know that the best is behind us. We are fortunate to have lived when there was still a certain amount of style and manners, and people still had a heart. Now it’s all so cheap, tawdry, shoddy, and people do not seem to have any feelings left. As for the world of opera, I cringe.” It would be tempting to dismiss these as the thoughts of an exhausted geriatric whose gaze is turning away from this world and peering into the next. Yet our contemporary preoccupation with visual spectacle, the diminishing and even cold-hearted mockery of musical integrity would appear to suggest otherwise. That guilty conscience is nipping at my heels once more…

For all the sensation that Pons’ physique once inspired, all we have left now is her voice—as fresh as it ever was. Miles Kastendieck of the New York Journal-American wrote on the day after she celebrated her 25th season at the Metropolitan that she was “perhaps the last of a long line of coloraturas who made their singing the be-all and end-all of their art.” A timeless lesson for aspirants to operatic greatness: The beauty which Lily Pons, her singing contemporaries, and their forebears embodied was more than just skin-deep.